IMPOSSIBLE RUBBER BANDITRY

(DRAFT: Liable to change)

Aaron Sloman

School of Computer Science, University of Birmingham

Installed: 6 Jan 2017

Last updated: ... ; 1 Nov 2017; 16 Mar 2021; 18 Apr 2022

4 Aug 2017: Added wrapped picture Figure 2 and a new argument.

This document is

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/rubber-bands.html

A PDF version may be added later.

A partial index of discussion notes is in

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/AREADME.html

What can't be done with a chain of linked rubber bands?

Previous title: What can be done with a chain of linked rubber bands?(Altered 23 Jan 2017)

Two pictures of the same chain of rubber bands are below. You can probably see how many bands there are and the 3-D shape taken by each rubber band. Although all the bands came out of the same packet, the linking process changed the 3-D shapes of most of them. One shape is different from the rest. We'll return to that below.

Suppose you grasp the two end bands firmly, one in each hand: there will then be many movements you can perform without letting go: shaking the bands, stretching them (i.e. pulling the ends further apart) twisting them, looping the chain over a door handle and pulling, winding them round a candlestick, etc. Is there any action you can perform while holding the two ends that will cause the rubber bands to come apart without breaking or being cut? If not, why not?

It is fairly easy to visualise changes made by adding or removing bands

You probably find it obvious that as long as more rubber bands are available they can be added to one or other end of the chain, while preserving the pattern of connections. Can you visualise the process of adding a new band to the chain at either end?The bands have been joined in such a way that each band except the left-hand end band has an asymmetric shape: at the left hand end the last band forms a simple loop, while at the right hand end there are two loops, with the next band going through them.

To maintain the pattern of connections in the picture, you would have to add new bands to the two ends in different ways. Can you visualise what would be required to add a band at either end? How would the processes have to be constrained if you wished to maintain the regular pattern of connections?

How might the chain look different if you added bands without maintaining the regular pattern? Would it be possible to produce alternating types of connection between bands?

What shapes can be formed by connecting a new band to a non-end band in the chain? E.g. could you form a "K" shape instead of a linear shape? Could the bands be linked to form a branching tree shape, with three branches added at every node?

A harder(?) question:

Can linked rubber bands close up to form a loop?

Is it possible to join the two end bands of the chain in the same way as the pairs of adjacent bands are joined, i.e. by pushing a loop in one end band through the other end band then pulling the rest of the band through its loop? This would close up the chain of bands to form a large loop.

Figure 2 shows what a chain of rubber bands stretched around another object, and joined out of sight to form a closed loop would look like!

If that cannot be done, then why not?

Many more examples, of different types of impossibility, are presented here:

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/impossible.html

Could a current AI learning engine be trained to distinguish things that are possible from those are impossible (although they can be described, or depicted)?

It is impossible for statistics-based forms of learning (e.g. those used in Deep Learning), whose form of learning produces useful probability estimates, ever to discover that something is impossible, or that certain features of an object or process makes possession of other features by that particular object or process impossible. It requires a different sort of cognitive mechanism about which, as far as I know, current neuroscience tells us nothing.

That's because the modal concepts "necessarily true" and "impossible" are completely different from the concepts of very high and very low degrees of probability, which whose application can be based on statistical evidence.

There are AI theorem provers that can tell whether a particular formula is provable within a system of axioms and rules, for certain classes of formulae. This requires the theorem prover to incorporate "meta-knowledge" about its own operation. Proving that there is no proof whose length is less than N steps can typically be done by exhaustive search. Demonstrating that there is no proof of any length is usually much more difficult. Questions of this sort can lead to undecidability results in mathematics, logic and AI.

Are there also undecidability theorems waiting to be proved regarding mechanisms in human brains? Answers may depend on which resources are available outside the brain, e.g. drawing facilities such as pencil and paper, or 3-D structures that can be manipulated to explore possible configurations.

Question for mathematicians:

Is this loop-closing impossibility a known theorem in 3-D topology, or a special

case of a known theorem? What sort of proof of impossibility of closing the loop

would satisfy modern mathematical standards of rigour? Are there universally

agreed standards? How are they justified?

How can non-mathematicians find it obvious that closing the loop is impossible

(perhaps after a little thought). I have asked a few, who did not take long to

decide it was impossible, though they did not find it easy to say why not?

What brain mechanisms make such processes possible? How did they evolve? How do

they develop in individuals? Do they exist only in brains of individuals with

mathematical training?

Do the mechanisms for spatial reasoning available to an individual brain depend

on the environment, and the opportunities it provides for learning to do various

kinds of spatial reasoning (e.g. the sorts of reasons used by ancient

mathematicians who made geometrical and topological discoveries long before

attempts were made to formalise spatial modes of reasoning)?

Why is the impossibility hard to explain?

What is the role of the assumption that no part of a rubber band can pass

through another part of a rubber band?

Related question: what kind of visual mechanism, or reasoning mechanism, makes it possible to discover that IF the rubber bands are indefinitely stretchable (so that size and thickness differences do not produce obstacles) THEN:

(a) it is always possible to link an isolated pair of rubber bands using the procedure mentioned (producing a two-link chain)?I am assuming that anyone who reads and understands (c) will agree that the process is impossible, but most non-mathematicians (and some mathematicians) will find it difficult to explain why. If I am wrong and it is possible, please let me know how. If possible please provide a video of the process, or a sequence of snap-shots.

(b) it is always possible to extend such a chain by linking a new isolated rubber band to an end band?

(c) it is never possible to transform such a (linear) chain into a looped chain by pushing a loop in one end band through the other end band then pulling the rest of the first band through its loop?

An interesting argument for impossibility

In July 2017, I received an interesting suggestion outlining a potential proof

of impossibility of closing the chain (without cutting and rejoining portions of

a rubber band) from Leila Sloman

https://mathematics.stanford.edu/people/leila-sloman

and David Sherman (at that time both PhD students at Stanford University)

They suggested starting from the observation that if the loop were closed as hinted in Figure 2, it could not be "opened up" (without cutting and rejoining a band) to form a linear chain of the sort depicted in Figure 1.

I agree that this does somehow "feel" impossible in a way that is different from perceiving the impossibility of starting with an open chain as in Figure 1 and transforming it to an closed chain without cutting and joining.

A summary of their argument as I understand it:

A configuration consisting of a closed loop of linked rubber bands cannot be opened up by unlooping one of the rubber bands, since attempting to do that that would end up pulling that band back in a circle to the same place it started.

Try to visualise undoing one of the links depicted in Figure 2.The fact that the loop cannot be undone would need to be proven rigorously. How could this be done? Is there a relevant known theorem about knots?

Impossible process vs impossible structure

NB I am not saying that it is impossible for a complete circular chain of

rubber bands to exist: merely that it is impossible to produce one

from a collection of existing rubber bands without introducing a temporary

discontinuity in any of the bands.

If the final band is somehow "grown" in place, or a band is cut, looped as required, and then the cut fused so that the join is invisible, then, the result could be a complete circular chain of linked rubber bands. So it's not a type of object that's claimed here to be impossible, but a type of process.

Can any currently existing automated theorem prover cope?

Is there any automated theorem prover that can make the sort of discovery

described above and prove the impossibility? I assume all the deep-learning

technology is irrelevant, since it does not (cannot) yield knowledge about

what's impossible, or necessarily the case, or mathematical implications. That's

because impossibility and necessity are not low and high extremes of

probability: they are concepts in a different space.

Many aspects of Euclidean geometry are concerned not with static structures (despite the frequent use of static diagrams) but with invariant features of processes that produce or modify structures. For example, invariant aspects of areas, or changes of areas, of triangles as the triangular shape (and/or position, orientation, or size) vary are summed up in theorems about areas of planar triangles as illustrated here:

Hidden Depths of Triangle Qualia (Especially their areas.)A separate file The Triangle Sum Theorem discusses ways of demonstrating that changing the size or shape of a planar triangle will not alter the sum of the interior angles.

Old and new proofs concerning the sum of interior angles of a triangle.

(More on the hidden depths of triangle qualia.)

I suspect that biological evolution produced mechanisms for (proto-mathematical?) reasoning about deformable structures that are not exactly planar, and do not involve infinitely thin or infinitely long or perfectly straight lines, long before the development of Euclidean geometry.

However, not all the organisms that can use such mathematical reasoning (e.g.

monkeys peeling bananas?) are aware that they are doing so and can discuss their

reasoning with others. That includes pre-verbal human toddlers, as illustrated

in this document:

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/toddler-theorems.html

Meta-Morphogenesis and Toddler Theorems: Case Studies

I think this is all connected with what James Gibson famously referred to as perception of "affordances" (including opportunities and obstacles for possible actions), though I don't know whether he ever noticed the connection with ancient mathematical discoveries. As far as I know he was not able to specify mechanisms for detecting and reasoning about affordances, except in a few special cases.

J. J. Gibson,

The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception,

Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA, 1979,

A limiting case

Some readers may have noticed that the impossibility "theorem" also applies to a chain consisting of only one rubber band: it can't be looped with itself to make a "closed" chain in the way that it can be linked to another band. It took me a couple of weeks to notice that.Example provided by Norman Megill 9 Sep 2021

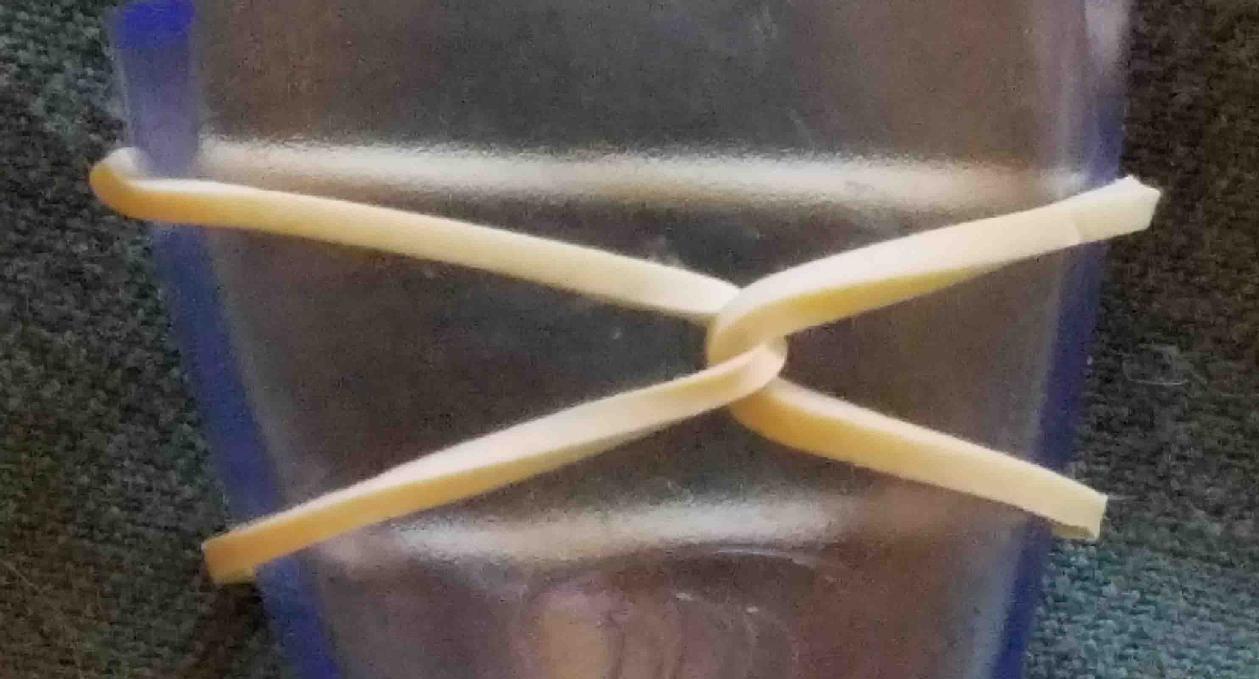

After I posted a question about the chain of rubber bands to the 'fom' (Foundations of Mathematics) discussion list, Norman Megill (co-author of Metamath http://us.metamath.org/) sent me this image (reproduced here with his permission):

He wrote:

While this doesn't answer your question, it reminded me of a simple trick that has fascinated children (and maybe some adults). Perhaps you will find it amusing.My initial reaction was "That's easy". I picked up a rubber band and mug -- and failed. I then looked back at the picture and realised I needed two twists, not just one! Details are left to the reader!First you hold a rubber band with one end of the loop in each hand, and ask how to connect the ends together, which seemingly would require passing the rubber band through itself. Many people will think it's impossible. Then with some quick manipulations, you produce the configuration in the attached picture. After putting the rubber band back to normal, some people still can't produce the configuration in the picture, and it's fun to watch them struggle.

I don't know if this is a standard trick. I came across it by accident while playing with a rubber band a few years ago.

Toddler topology

Human mathematical competences involving abilities to notice and describe spatial possibilities and impossibilities, and to reason about them, grow out of abilities that evolved much earlier and are (in some cases) shared with other intelligent species (e.g. squirrels, elephants, apes, nest-building birds, hunting mammals). Even pre-verbal human toddlers/crawlers seem to have have (unreflective) geometrical and topological reasoning abilities, such as the 17.5 month child in this video:http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/movies/ijcai-17/small-pencil-vid.webm

At present, I don't think anyone knows how these abilities to discover and make

use of spatial possibilities, impossibilities and necessities (another aspect of

impossibilities) evolved or how the abilities are implemented in brains. Logic

based automated theorem provers do something completely different from the

reasoning of ancient mathematicians, squirrels, toddlers, etc. Some half-baked

ideas about how some of these abilities evolved (using what Jackie Chappell and

I call "meta-configured genomes") can be found here, including a short video

explaining part of the theory:

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/movies/meta-config

Ways of using rubber bands combined with (e.g.) bits of wire in a loop

https://www.wikihow.com/Make-a-Rubber-Band-Necklace

RELATED DOCUMENTS

This document is one of many presenting examples of perception of possibilities

and impossibilities (involving geometry, topology, and numbers) on this web

site. Here are some more of them (including those already mentioned above):

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/triangle-sum.html

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/trisect.html

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/triangle-theorem.html

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/impossible.html

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/torus.html

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/shirt.html

Another challenge for automated reasoning systems -- discover/invent a 3-D

ontology in order to explain/understand sensed 2-D phenomena:

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/nature-nurture-cube.html

This is part of the Turing-inspired Meta-Morphogenesis project:

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/meta-morphogenesis.html

A long term project: specify a Super-Turing reasoning machine capable of making

these discoveries and explaining them:

http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/super-turing-geom.html

REFERENCES AND LINKS (to be added)

Maintained by

Aaron Sloman

School of Computer Science

The University of Birmingham